The streaming economy has entered a new phase. After a decade of venture-funded subscriber acquisition at any cost, major platforms have pivoted toward profitability. Netflix now generates $7 billion in annual operating income, for example, and Disney+ finally achieved operating profit after years of losses. This shift toward sustainable economics creates pressure throughout the media ecosystem including on the creative workforce that produces the content these platforms distribute.

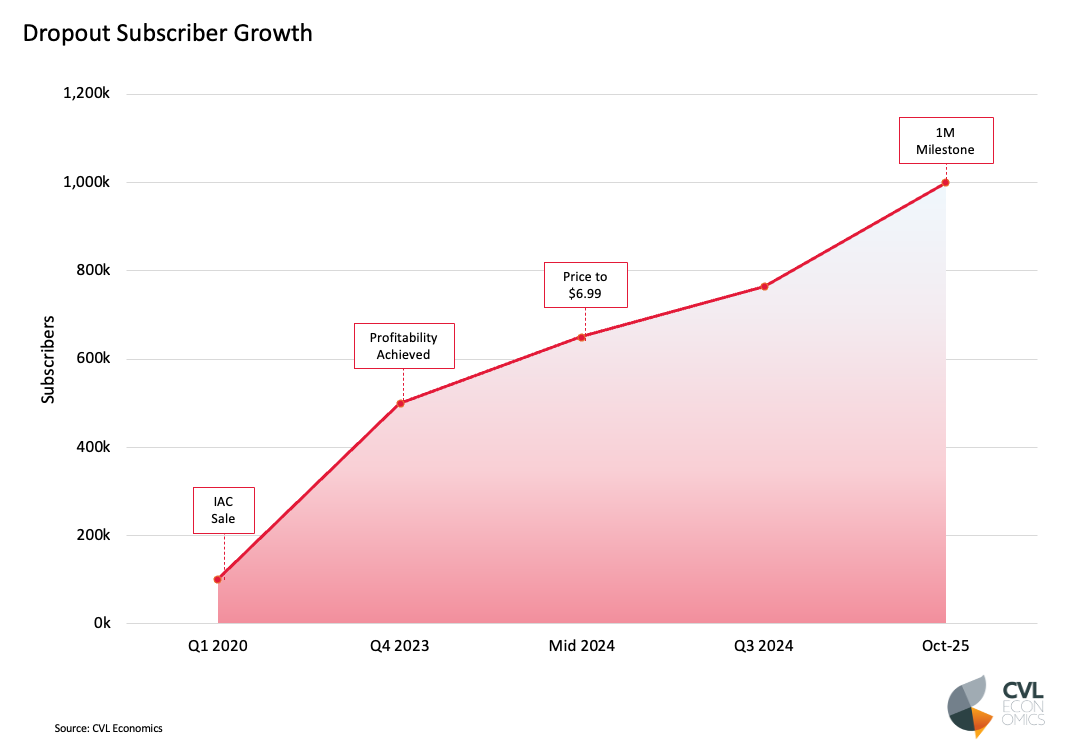

Against this backdrop, a small but instructive category of media companies has emerged: creator-owned, direct-to-consumer subscription platforms that bypass both traditional distributors and the algorithm-dependent economics of ad-supported social media. Dropout, a comedy streaming service that grew from near-bankruptcy to over 1 million subscribers with estimated earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) margins of 40–45 percent, offers a useful lens for examining what these alternative models mean for creative labor and media economics.

The Structural Difference of Creator Ownership

Most digital media companies operate under one of two dominant models. Venture-backed platforms prioritize growth metrics (subscribers, views, engagement) that justify future fundraising and an eventual exit to public markets or strategic acquirers. Advertising-supported platforms optimize for algorithmic distribution and viewer attention, subject to the monetization priorities and content policies of third-party platforms like YouTube or TikTok.

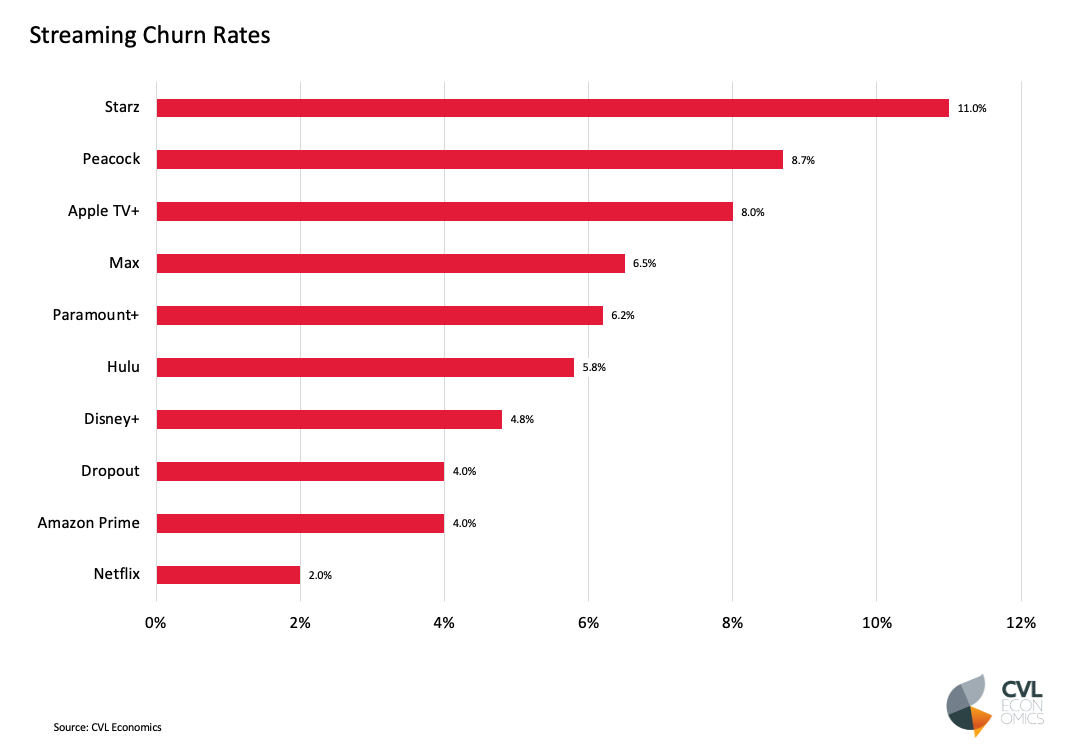

Creator-owned platforms operate under different conditions. When the majority owner is also the creative principal, operational decisions can prioritize sustainability over growth velocity. This shows up in measurable ways. Dropout maintained the same subscription pricing for over three years while competitors raised prices annually. When the company finally increased prices in 2025, existing subscribers were grandfathered in at legacy rates. More over, the company explicitly encourages password sharing—a behavior that Netflix and other major streamers have systematically cracked down on to drive subscriber conversions.

These decisions would be difficult to justify under venture capital pressure or public market scrutiny. They are possible because the ownership structure allows prioritizing subscriber relationships over near-term revenue extraction.

Trade-offs: Sustainability vs. Scale

Direct-to-consumer subscription models offer meaningful advantages for creative operations. Revenue arrives monthly with high predictability, independent of platform algorithm changes that can devastate ad-supported creators overnight. Subscriber retention provides a stable planning horizon for production investments. The absence of advertising intermediaries means creators capture a higher share of each subscriber dollar.

But these benefits come with structural constraints. Niche content categories have market ceilings. Analysis of the comedy streaming category suggests Dropout may already have reached 50 to 67 percent penetration of its total addressable market globally. This creates tension: sustainable operations require continued subscriber growth to absorb rising costs and fund new content, yet organic market limits constrain expansion without moving into adjacent content categories where core competencies may not transfer.

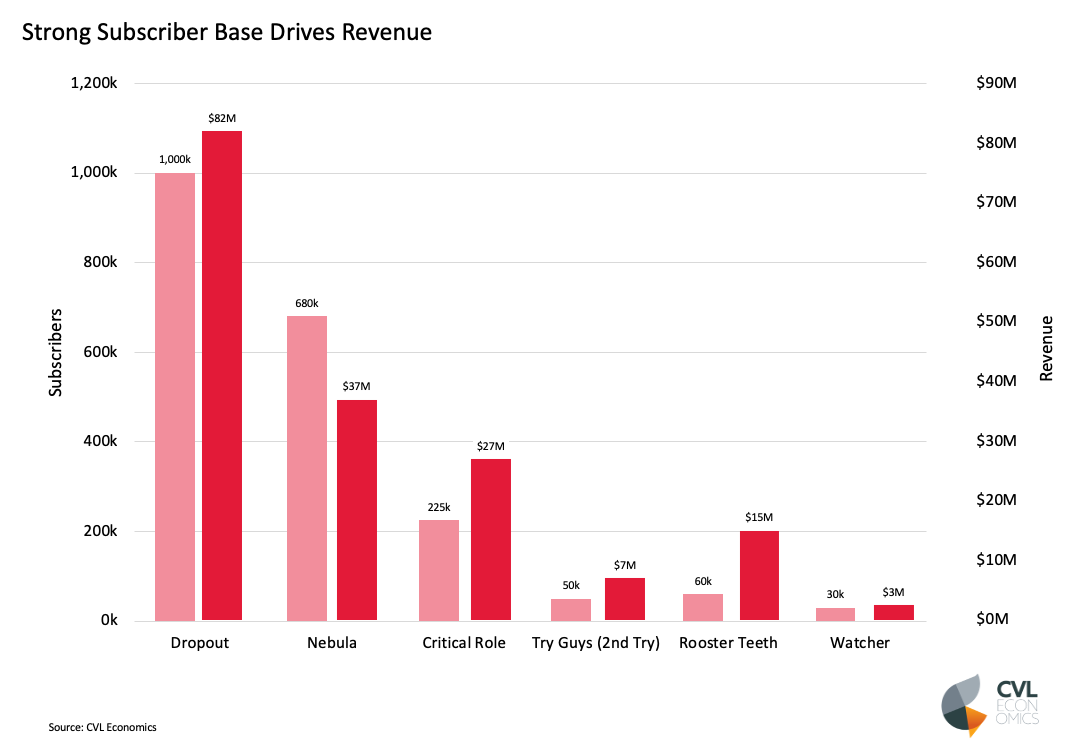

The March 2024 shutdown of Rooster Teeth—a creator platform with over 20 years of operation, mainstream intellectual property, and Warner Bros. Discovery backing—illustrates how quickly success can reverse. At its peak, Rooster Teeth had 225,000 paying subscribers; at closure, that number had fallen to 60,000, eliminating approximately 150 jobs. These are not abstract market dynamics. They represent the direct economic security of creative workers.

Implications for Creative Labor

Dropout's operational model offers one structural experiment in creative worker compensation. The company distributes profits to all contributors including project-based contractors, crew members, and even individuals who auditioned but were not cast. With estimated EBITDA margins of 40 to 45 percent on $80–90 million in revenue, this profit pool is substantial. The model shares economic upside more broadly than the typical work-for-hire arrangements that dominate digital media production.

At the same time, platforms like Dropout rely heavily on contractor classification rather than W-2 employment. Of the company's reported 27 full-time employees, on-screen talent and production crew are engaged project-by-project. This arrangement provides flexibility for both company and workers, but it also shifts responsibility for benefits, retirement savings, and income volatility onto individuals. The trade-off between profit participation and employment stability reflects broader tensions in creative economy labor structures.

The capital efficiency enabled by this model is striking. Dropout generates an estimated $3.0 to $3.3 million in revenue per full-time employee, compared to $200,000 to $500,000 typical for traditional production companies. This efficiency derives partly from the unscripted, improvisational content format that requires minimal post-production compared to scripted or animated programming. Whether this efficiency benefits workers through profit-sharing or simply enables higher margins depends entirely on governance decisions that creator ownership makes possible but does not guarantee.

Relevance for Policy and Economic Strategy

The existence of profitable, creator-owned media platforms at scale provides useful evidence for policy discussions about media market structure and creative workforce conditions. These platforms demonstrate that alternatives to advertising-dependent and conglomerate-controlled distribution are technically and economically viable, though they require access to shared infrastructure (in Dropout's case, Vimeo OTT's white-label streaming technology) to achieve cost-effective operation.

For regional economic development, these models suggest that viable creative production ecosystems do not necessarily require proximity to legacy entertainment centers or dependence on venture capital concentration. Subscription-funded platforms can support production operations wherever creative talent and production capacity exist. The limiting factor is audience development and retention—functions that increasingly occur through digital channels independent of physical location.

For labor organizations and workforce development entities, the emergence of profit-sharing contractor models presents both opportunities and challenges. These arrangements offer creative workers participation in economic upside typically reserved for owners and investors. But they do not address fundamental questions about benefits access, income stability, and the long-term career sustainability of project-based creative work. The hybrid nature of these models, which are neither traditional employment nor pure gig economy, may require correspondingly hybrid policy frameworks.

What This Case Illustrates

Dropout is one company operating in one content niche with specific ownership circumstances. Its success does not provide a universal template for creator-owned media, and its structural vulnerabilities (namely, talent concentration, addressable market constraints, execution risk in content expansion) limit direct replication. The Rooster Teeth precedent demonstrates that comparable models can fail despite scale and corporate backing.

What the case does illustrate is that the dominant models of digital media are not the only viable paths. Subscription-funded, creator-owned platforms can achieve profitability and sustain creative production at meaningful scale while implementing compensation structures that share economic returns with the workforce. Whether such models can scale beyond niche categories, survive leadership transitions, and maintain their stakeholder-oriented governance under growth pressure remain open questions.

For policymakers, economic development practitioners, and labor organizations, these alternative structures merit attention not as solutions but as evidence that different configurations of media production economics are possible. Understanding how they function—and where they fail—informs more grounded discussions about the future of creative work.

RELATED CONTENT